Trang Nguyen*, Dung Le, Huy Nguyen, Khai Nguyen, Nhat Ho

Improving Mini-batch Optimal Transport via Partial Transportation

1. Introduction

The Optimal Transport (OT) theory has a long history in Applied mathematics and economics, and recently it has become a useful tool in machine learning applications such as deep generative models [1], domain adaptation [2], etc. Despite its popularity in ML, there are still major issues of computation cost with using OT in large-scale datasets, those issues could be demonstrated in two following situations: “What if the number of supports is very large, for example millions?” and “What if the computation of optimal transport is repeated multiple times and has limited memory e.g., in deep learning?”. To deal with those problems, practitioners often replace the original large-scale computation of OT with cheaper computation on subsets of the whole dataset, which is widely referred to as mini-batch approaches [3, 4]. In particular, a min-batch is a sparse representation of the data. Hence, matching two sparse subsets of two datasets often leads to many wrong pairings between sample points of two distributions. That consequently results in the extremely inaccurate estimation of the transport plan and OT cost between distributions.

2. Background

2.1. Optimal Transport

Let be discrete distributions of

supports, i.e.

and

. Given distances between supports of two distributions as a matrix

, the Optimal Transport (OT) problem reads:

(1)

where is the set of admissible transportation plans between

and

.

Figure 1. An example of OT with n = 4.

2.2. Mini-batch Optimal Transport

The original samples are divided into random mini-batches of size

, then an alternative solution to the original OT problem is formed by averaging these smaller OT solutions.

(2)

where denotes product measure,

is the sampled mini-batch, and

is the corresponding discrete distribution. In practice, we can use subsampling to approximate the expectation, thus the empirical m-OT reads:

(3)

where and

is often set to 1 in previous works.

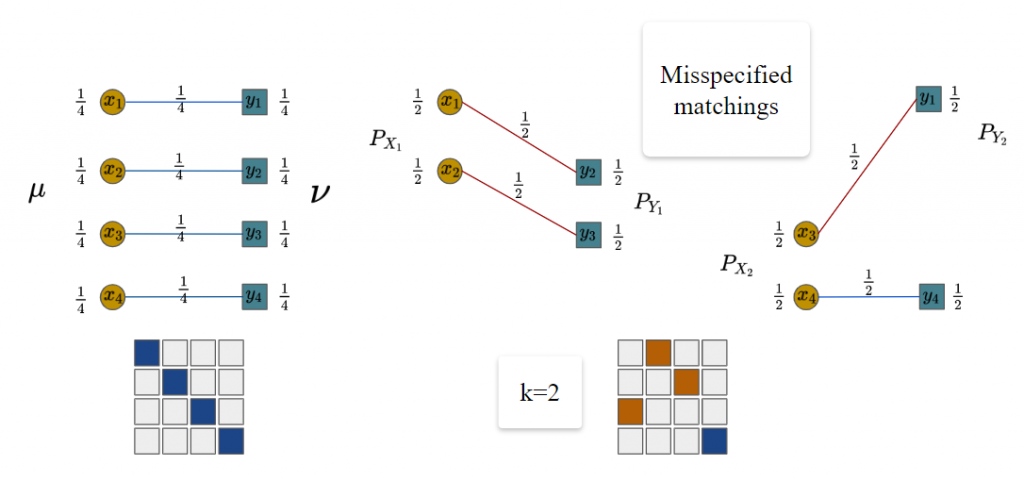

Misspecified matchings issue of m-OT

We can see that the optimal matchings at the mini-batch level in Figure 2 are different from the full-scale optimal transport. We call these pairs misspecified matchings since they are optimal on the local mini-batch scale but they are non-optimal on the global scale. The reason is that all samples in mini-batches are forced to be transported.

Figure 2. An example of m-OT with n = 4, m = 2 and k = 2.

3. Mini-batch Partial Optimal Transport

To alleviate misspecified matchings, we use partial optimal transport between mini-batches levels instead of optimal transport. The partial optimal transport is defined almost the same as optimal transport except it only allows a fraction of masses to be transported.

3.1. Partial Optimal Transport

Let be discrete distributions of

supports. Given the fraction of masses

, the Partial Optimal Transport (POT) problem reads:

(4)

where is the set of admissible transportation plans between

and

.

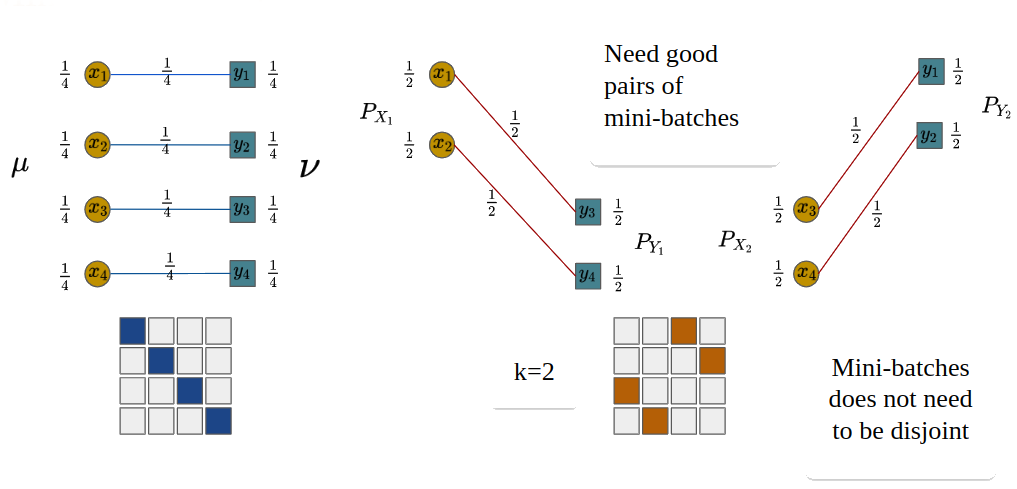

3.2. Mini-batch Partial Optimal Transport

Similar to m-OT, we define mini-batch POT (m-POT) which averages the partial optimal transport between mini-batches of size as:

(5)

where denotes product measure,

is the sampled mini-batch, and

is the corresponding discrete distribution. In practice, we can use subsampling to approximate the expectation, thus the empirical m-POT reads:

(6)

where and

is often set to 1.

Figure 3. An example of m-POT with and

.

In Figure 3, POT gives the exact 2 matchings, alleviating the misspecified matchings issue.

3.3. Training deep networks with m-POT loss

Parallel training

In the deep learning context, the supports are usually parameterized by neural networks. In addition, the gradient of neural networks is accumulated from each pair of mini-batches and only one pair of mini-batches are used in memory at a time. Since the computations on pairs of mini-batches are independent, we can use multiple devices to compute them.

Two-stage training

We also propose two-stage training for *domain adaptation*. We first find matchings between pairs of bigger mini-batches of size on RAM. Then use it to obtain a mapping to create smaller mini-batches of size

which are used on GPU for estimating the gradient of neural networks. This algorithm allows us to have better matchings since they are obtained from larger transportation problems.

4. Experiments

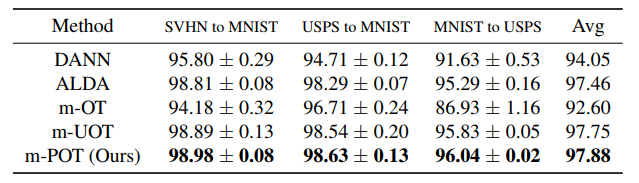

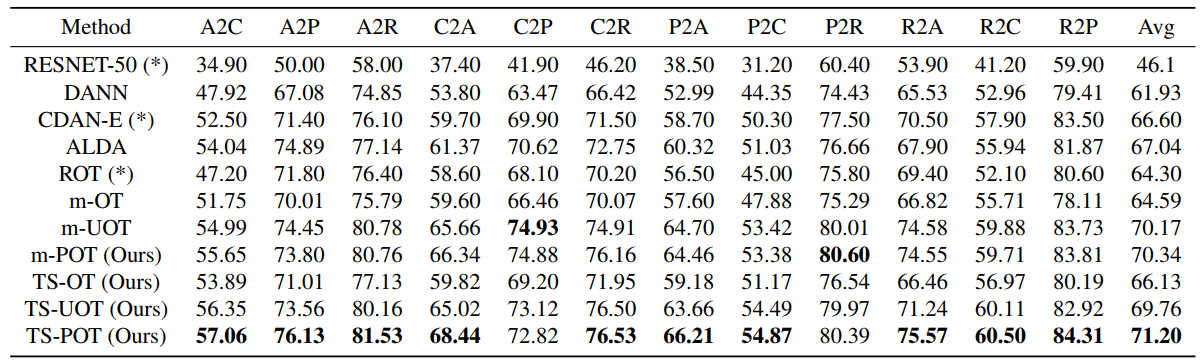

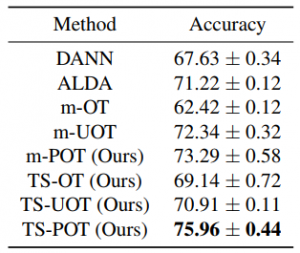

To validate the performance of the proposed methods, we carry out experiments on deep domain adaptation (DA). We observe that m-POT gives better-adapted classification accuracy on all datasets than the previous methods. Moreover, the two-stage training significantly improves the performance of DA on Office-Home and VisDA for both optimal transport and partial optimal transport.

Table 1. DA results in classification accuracy on digits datasets (higher is better).

Table 2. DA results in classification accuracy on the Office-Home dataset (higher is better).

Table 3. DA results in classification accuracy on the VisDA dataset (higher is better).

5. Conclusion

In this paper, we have introduced a novel mini-batch approach that is referred to as mini-batch partial optimal transport (m-POT). The new mini-batch approach is motivated by the issue of misspecified mappings in the conventional mini-batch optimal transport approach (m-OT). Via extensive experiment studies, we demonstrate that m-POT can perform better than current mini-batch methods including m-OT and m-UOT in domain adaptation applications. Furthermore, we propose the two-stage training approach for the deep DA that outperforms the conventional implementation. For further information, please refer to our work at https://proceedings.mlr.press/v162/nguyen22e/nguyen22e.pdf.

References

[1] Arjovsky, M., Chintala, S., and Bottou, L. Wasserstein generative adversarial networks. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pp. 214–223, 2017.

[2] Courty, N., Flamary, R., Tuia, D., and Rakotomamonjy, A. Optimal transport for domain adaptation. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence, 39(9):1853–1865, 2016.

[3] Fatras, K., Zine, Y., Flamary, R., Gribonval, R., and Courty, N. Learning with minibatch Wasserstein: asymptotic and gradient properties. In AISTATS 2020-23nd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, volume 108, pp. 1–20, 2020.

[4] Fatras, K., Zine, Y., Majewski, S., Flamary, R., Gribonval, R., and Courty, N. Minibatch optimal transport distances; analysis and applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:2101.01792, 2021b.

Overall

Dang Nguyen – Research Resident

Share Article